About Marion Shoard

I was born in the west of Cornwall in 1949 and spent most of my childhood in Ramsgate, east Kent. I read zoology at Oxford University and, in order to work in countryside conservation, spent two years at the then Kingston-upon-Thames Polytechnic, studying town and country planning.

Environment

I then worked for four years at the national office of the Council for the Protection of Rural England (CPRE), campaigning in fields ranging from national parks to forestry, and rural public transport to wildlife conservation. However, I had become more and more convinced that the main threat to the beauty and diversity of England's countryside was the expansion and intensification of agriculture and, with the help of a grant from the Sidney Perry Foundation, I left CPRE to research and write The Theft of the Countryside (1980).

This book struck a chord with the public and sparked off a lively debate, with thirty letters published in The Times, for example. During the following few years I wrote articles and gave talks on the book’s theme, lobbied on rural issues in Parliament and helped set up countryside action groups. The Theft of the Countryside included proposals to establish new national parks in lowland England.

A second book, This Land is Our Land (1987), examined the history of the relationship between landowners and the landless, and suggested it should be placed on a new footing. This book also attracted attention.

![]()

I presented a one-hour documentary on its subject matter made by London Weekend Television for Channel 4 and called Power in the Land.

During the next few years, I wrote numerous articles and gave many talks about a wide range of rural issues. I also taught countryside planning and land management to students at universities, including Reading and University College London. Gaia Books reissued This Land is Our Land, expanded and updated, as a Gaia Classic in 1997.

One element of the arrangements I had put forward in This Land is Our Land was the replacement of the UK's trespass régime with a general right of public access to the countryside, providing much greater freedom to roam.

With the help of grants from the Nuffield Foundation and The Leverhulme Trust, I set to work out how such a right could operate on the ground, which would afford the public as extensive access as possible while ensuring privacy were not invaded nor legitimate uses of the countryside harmed. This involved making trips to Scandinavia, France and Germany to see for myself the very different access systems operating in those countries and examining on the ground how wider access might operate in different typesof terrain in the UK. Oxford University Press published my conclusions in A Right to Roam (1999), which was acclaimed as Environment Book of the Year in 2000 by the Outdoor Writers Guild.

Three years later, I was delighted by the passage into law of the Land Reform (Scotland) Act 2003, one of the first pieces of legislation enacted by the new Scottish Parliament. This provides the public with a statutory right of responsible access to land and water and stands in stark contrast to the partial, and in my view half-baked, right of access which the Countryside and Rights of Way Act introduced in 2000 for England and Wales, which applies mainly to mountain and moorland and leaves unaffected much of the lowland countryside closest to where most people live.

In 2005, I supported Jean Perraton’s call for a right to swim in inland waters in the UK, through penning the foreword to her book Swimming against the Stream: Reclaiming Lakes and Rivers for People to Enjoy ![]() .

.

In 2020, the Covid pandemic unleashed a wave of visiting the countryside. This has downsides for those of us urging the extension of rights of access for walkers. TV and the press featured images of the discarded beer cans and tents visitors had left behind together with sheep terrified by townspeople's dogs. This has been coupled with the realisation that many people who wish to have greater access to the countryside will not limit themselves to quiet strolling, but carry out potentially disruptive activities, from flying drones to exercising dogs or speeding on e-bikes. It is important that the access movement should address this new reality head on. The case for the introduction of a universal right to be present on land and water (as opposed to a continuation of the partial approach promoted by Nick Hayes and Guy Shrubsole's Right to Roam campaign launched in 2020) is as compelling as ever, but it is important that this should be accompanied by a recognition of the real conflicts which are occurring through the unambiguous restriction of potentially damaging recreation pursuits in particular places and the zoning of other areas in which they are clearly permitted.

My activities over the years in the environment sphere have been profiled in the following feature articles:

- Original thinker and influential environmentalist Marion Shoard talks to Alex Reece

The Simple Things, April 2018

The Simple Things, April 2018

(The Simple Things is available to buy on the news-stand or on the web, at thesimplethings.com.) - Tunnel Vision

by Stephen Neale, Outdoor Focus, Summer 2014

by Stephen Neale, Outdoor Focus, Summer 2014 - The Essential Marion Shoard

by Jim Perrin, The Great Outdoors, November 2000

by Jim Perrin, The Great Outdoors, November 2000 - Accessing All Areas

by environment journalist Caron Lipman, Planning, 11 June 1999.

by environment journalist Caron Lipman, Planning, 11 June 1999.

I was a part-time lecturer in countryside planning at Reading University, the University of Westminster and University College London during the late 1980s and 1990s.

Older People's Affairs

In 1999, just as A Right to Roam was being published, I suddenly found myself pitched into a very different world. My mother, then in her mid-80s and still living in Ramsgate, was developing dementia. Suddenly I was facing big decisions for which I was unprepared. Should I look after my mother myself? Should she go and live in a care home and, if so, how could I choose one I could trust?

After a long struggle, I managed to secure good care for my mother in a long-term NHS facility. I then set about assembling the advice I wished had been available to me during what had proved the most traumatic period of my life.

After a long struggle, I managed to secure good care for my mother in a long-term NHS facility. I then set about assembling the advice I wished had been available to me during what had proved the most traumatic period of my life.

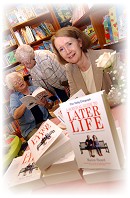

In A Survival Guide to Later Life (2004), I sought to provide comprehensive and straight-talking guidance not only for the relatives of frail elderly people but also for older people themselves, since I realised that my mother's final years could have turned out much better had she done some contingency planning. In 2017 my new book was published. How to Handle Later Life is far longer than the Survival Guide and largely replaces it. You can see the contents and four sample sections here. There is more information about my involvement in the world of older people here.

I now involve myself in both environment affairs and older people's issues. I give talks, write articles and take part in television and radio discussions, sometimes offering guidance, at other times opinions and proposals to improve situations. I am a vice-president of the British Association of Nature Conservationists and have been a trustee of the Relatives and Residents Association (which seeks to help care home residents and their families). My involvement with the Alzheimer's Society, particularly in a group which evaluates research proposals, has brought me, circuitously and unintentionally, back to the zoology which fascinated me at Oxford fifty years ago. Since 2019, I have also volunteered with Healthwatch Medway and been a member of the executive committee of Christians on Ageing.